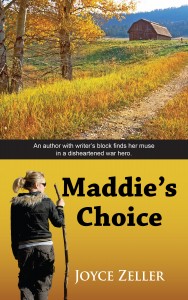

Writing Good Dialogue by Joyce Zeller, author of Maddie’s Choice, The Haunting of Aaron House and Love in a Small Town

Writing dialogue is the best part of creating a novel. I’m a dialogue junkie. If I start reading a book and I don’t see quotation marks by page 2; I’m out of there. Giving a character voice is like playing a part in a film. You have to be the character, get inside of them and feel the scene, the way it looks and smells. You learn this by constantly describing people and scenes in your mind all day, wherever you go. When you meet someone, describe them in your journal.

Most people use clichés when they speak, according to their culture. I live in the south, and one of my favorites is, “He’s a hard dog to keep under the porch.” They have speech patterns, and start sentences with, “Well, yeah…,” or “Back in the day…,” or end them with, “…just saying.” In the South, it is the double negative. “I don’t have no problem with that.” When teenagers are relating a conversation, they often start with, “He goes…” and then, “I go…” I like to give pet expressions to my characters. The sheriff’s wife in my romance, Maddie’s Choice, is a loud, buxom woman who ends a lot of her sentences with “…so to speak,” and has Maddie doing it sometimes.

Since I write women’s lit with romance, I create a female and a male main protagonist, and I’ll probably write in each one’s point of view, which means I have to know the character intimately before they speak—be in tune with the emotions governing their speech, as well as their background and sophistication. How do they feel at that moment? Okay, here’s a for instance: in Maddie’s Choice, set present day, at an Arkansas cattle ranch, Maddie Taylor is from New York, a successful writer of romances, and has inherited half of a ranch. She’s just arrived, greeted by a very hostile crowd. Clearly she’s not welcome. We’ve already met her in New York, so we know how she’s looked forward to living on a ranch, yearning for real friends. Disappointed, almost to tears, at their attitude, she loses her temper and explodes into a rant. Feisty Maddie has a smart mouth. Her speech will reflect her background as a successful writer—educated, with a large vocabulary at her command. She’s just been told Uncle Gid said, “She’s some Bimbo who just wants to take the money and leave.” To wit: Fueled by anger, she planted her bright red boots solidly, put her fists on her hips, and raged, “Whoever implied that is a sexist, judgmental, bigoted ignoramus who doesn’t have a clue, and has no business giving opinions on subjects about which he knows nothing. Where might I find this paragon of Western wisdom so that I might enlighten him?”

“Right here, ma’am. You have somethin’ to say to me?”

The deep voice came from right behind her, full of challenge, loaded with sarcasm, and entirely too close. She turned and looked into the eyes of Mister Sex, himself.

“I’m here to stay. Now, deal with it.”

“Well, hell.”

This is Gideon, the other half-owner, who has decided not to like her, although she excites him. He’s street-smart, and his speech reflects his gender. When he’s at a loss for words, he often says, “Well, hell.”

The following are snippets from a conversation Gid has with Pete, the grizzled senior citizen, foreman of the ranch for years and surrogate dad to young, orphaned Gideon. By now we know that Gideon is a damaged war veteran with PTSD, and although yearning for love, is afraid to get close for fear he’ll hurt someone. In this scene, Gid is sitting alone in the barn, depressed after another argument with Maddie, nearly drunk from a bottle of wine. Pete enters.

“Gid, what are you doing here? I thought you were with Maddie?”

Gideon gestured with the bottle. “Here, it’s some wine I found in the kitchen.”

Pete accepted the offer and took a drink. “Jesus,” he gasped, coughing, “what is this stuff?”

“Chardonnay. Maddie bought it for the party. She says New Yorkers drink it.”

Pete grimaced. “It wouldn’t be my poison of choice. Hell, I don’t like grapes on a bunch, why would I like ‘em in a bottle? Guess it gets the job done, though.”

Gid got to the point. “I don’t know a damned thing about women.”

“Women are different ‘n men,” Pete agreed with a nod.

“Ain’t that the damned honest truth?”

Gideon goes on to explain his latest dust-up with Maddie, his confusion, and despair. Pete tells him his problem. “Hell, boy. You’re already half in love with that woman.”

“I don’t believe in love. People don’t have it in them to give. This man-woman thing is all about sex. There’s no such thing as love. How would you know, anyway?” He raised the bottle to his lips “You’ve been married to Bea for more’n fifty years. Do you love Bea?” It took a lot of wine for him to find the nerve to ask that. A man his age shouldn’t be ignorant of such things.

Pete thought a bit. “In the morning I wake up, in this warm place that Bea and me made, with her curled up against me, holdin’ on to me like I was the most important thing in her world. No matter how my day goes, I know she’ll be there when I come home. The thought makes the day worth living. That’s how I know.”

I could have left the tags off all Pete’s speech because his words were so different from Gideon, you know who’s talking, but they serve to pace the scene, so I left some on.

Don’t be afraid of making your men human. Men bare their souls to each other in a heartfelt way that makes them no less men. The realization that men speak differently when they are among their own was pioneered by Paddy Chayefsky, a brilliant playwright of the 1950’s and his breakthrough play Marty (1955). His style was termed “kitchen realism.”

When Maddie is kidnapped, right before a gun battle with the local drug-smuggling motorcycle gang, Gideon’s army buddy shows up with the DEA. Rooney is Australian. That needed a lot of research into Australian slang. At the end of the last scene, after the gun battle, when Maddie’s life has been saved by an Angus bull, he remarks, “If the bikey comes good, he’ll need a new set of knackers. That bull made a mess of him.”

https://loiaconoliteraryagency.com/authors/joyce-zeller/ http://joycezeller.com/